Why Good Research Gets Overlooked: 6 Hidden Barriers in the Impact Pipeline.

Discover the hidden barriers that keep great research from making a real-world impact—whether in policy, practice, or commercialization. This post uncovers six common barriers in the research-to-impact pipeline and offers actionable insights to help researchers, institutions, and innovators unlock the true potential of their work.

Why Good Research Gets Overlooked: 6 Hidden Barriers in the Impact Pipeline.

Discover the hidden barriers that keep great research from making a real-world impact—whether in policy, practice, or commercialization. This post uncovers six common barriers in the research-to-impact pipeline and offers actionable insights to help researchers, institutions, and innovators unlock the true potential of their work.

When we talk about research impact, we often picture clear, linear pathways from publication to policy change, innovation, or public benefit. But in practice, impact is rarely that simple. Whether the goal is shaping policy, informing professional practice, or driving commercialization, many valuable research findings struggle to make it out of the academic sphere. This post explores six often-overlooked barriers that prevent good research from gaining traction beyond its original context, and what we can do to address them.

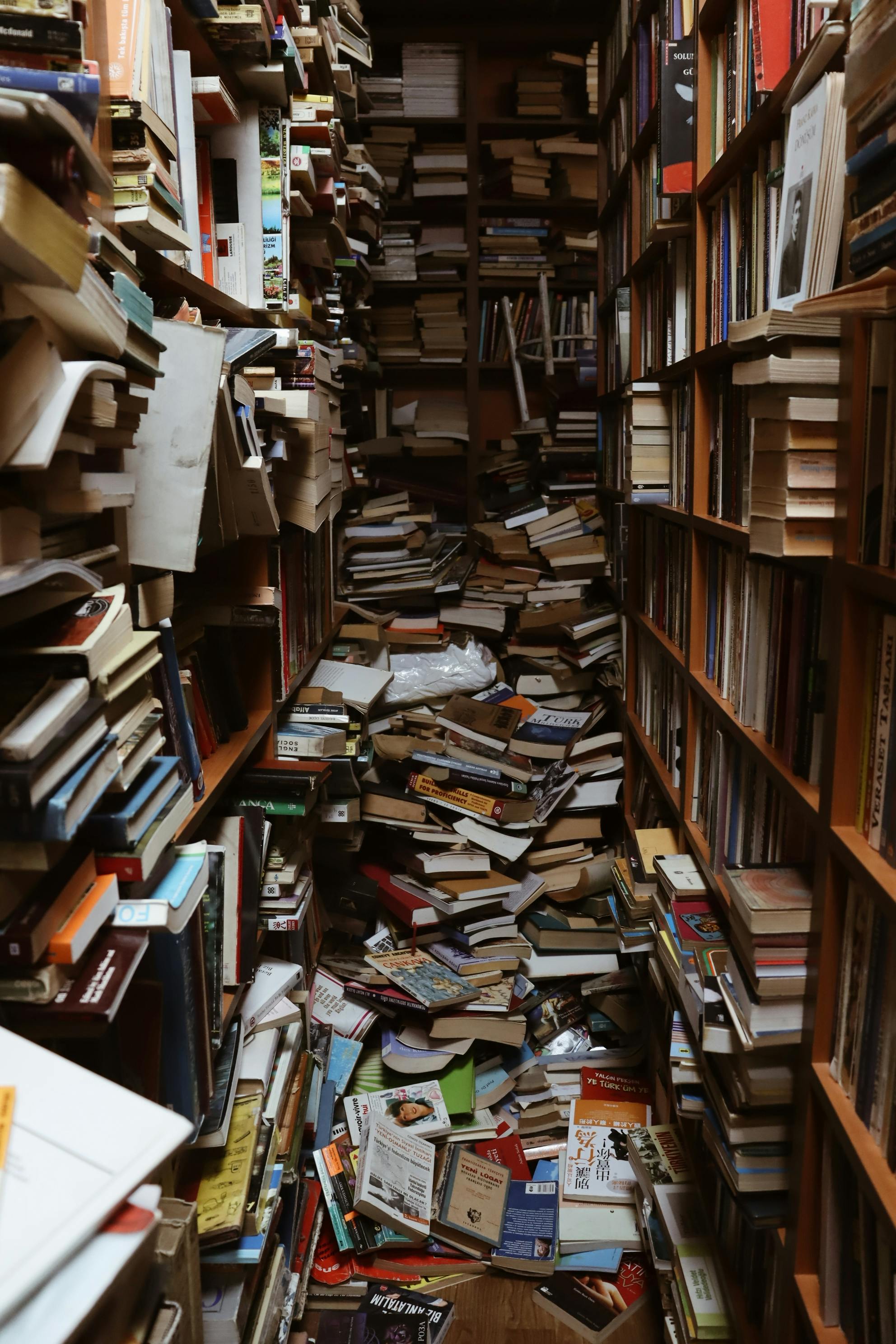

Impact isn’t a straight line from evidence to action—it’s a maze of relationships, timing, and relevance.

Barriers to Impact

1. Obscure Framing

We often imagine research impact as a straight and tidy path from evidence to action. But in reality, it’s more like a tangled web of relationships, timing, and context. As I explored in Innovation Lives Outside of the Comfort Zone, innovation and impact rarely fit into conventional categories.

This mismatch often results in obscure framing: when research is presented in ways that make its value hard to recognize, whether for policymakers, industry partners, NGOs, or the general public. If research is too embedded in academic jargon or framed in terms only meaningful within a discipline, it risks being invisible to those who could apply or commercialize it.

If research is only legible within academia, it risks being invisible where it matters most.

Oliver et al. (2014) found that lack of relevance and timing hinders policy uptake [1], but the same applies across sectors. Investors won’t back technology they don’t understand. Entrepreneurs won’t license findings that seem out of sync with market signals. Practitioners won’t pilot approaches that feel disconnected from lived realities.

Schot and Steinmueller (2018) argue that dominant R&D-centric innovation models often overlook socially-driven or community-based innovations [2]. Broader framings like sustainability transitions, human-centered design, or inclusive innovation can help align research with a diversity of real-world challenges and opportunities.

Good research deserves framing that highlights not just its theoretical contribution, but its practical, commercial, and social relevance.

2. Limited Discoverability

Even the most insightful research can’t generate impact if no one can find or understand it. Discoverability is a prerequisite for uptake across all sectors, from government to tech startups.

Open access improves visibility, and metadata standards enhance searchability, but both are just the beginning. Piwowar et al. (2018) found that on average, open access articles get more citations [3], but if they’re trapped behind paywalls, trapped in academic archives, hidden in dense academic PDFs or buried in obscure journals, their broader influence is still constrained.

Chiu et al. (2023) showed that user-centered metadata and search tools dramatically improve access [4]. The study found that commonly used metadata elements, such as author, publication year, and subject, combined with intuitive search facets, significantly influence how easily users can locate datasets. This suggests that discoverability depends not just on availability, but also on the quality of supporting infrastructure and user experience design.

Open access isn’t enough if no one can find or use what’s inside.

Moreover, discoverability requires translation. A biotech startup may not sift through dense academic prose to identify promising compounds. A nonprofit can’t implement a social intervention if key findings are buried in statistical appendices. Formats like explainer videos, open datasets, demo prototypes, design briefs, or policy memos can make research discoverable and usable to new audiences.

3. Weak Relevance Signaling

Too often, research outputs don’t clearly signal why they matter—to whom, for what, and in which context. This weak signaling can obscure value in policy conversations, commercial settings, or civil society applications.

Glasziou (2014) calls out the cost of incomplete or unusable reporting in biomedical science [5], but the principle holds more broadly. Vague methods, buried findings, and lack of real-world implications make it hard for partners to assess feasibility or risk.

Vague outputs don’t just fail to inspire—they fail to inform.

Clear relevance signaling means more than "implications for future research." It includes:

- Specifying end-users (e.g., clinicians, engineers, regulators, community leaders)

- Highlighting applications (e.g., business models, product improvements, program design)

- Demonstrating traction (e.g., early pilots, licensing interest, stakeholder feedback)

Oliver and Cairney (2019) advise researchers to actively shape and signal relevance across platforms, not just in journals [6]. That includes LinkedIn threads, demo days, podcasts, startup pitches, and policy memos.

If funders, policymakers, or practitioners can’t quickly see how your research aligns with their goals, timelines, or constraints, they’ll move on.

4. Misaligned Incentives

Even when research has impact potential, academic environments may not reward efforts to realize it. Incentive structures still favor scholarly metrics (like publication counts and impact factors) over patents, prototypes, public outreach, or partnerships.

Sormani et al. (2021) emphasize that researchers are motivated by a mix of curiosity, recognition, and social value [7]. Their research finds that subtle nudges, such as peer examples or awareness campaigns, often work better than extrinsic rewards, which can undermine intrinsic motivation. The study cautions against overreliance on financial incentives, which may backfire if they conflict with academic autonomy and values. Institutions that support engagement through mentorship, workload allowances, and career pathways create the conditions for broader impact.

What gets measured still decides what gets made.

Some universities are leading change. The University of New South Wales' Pact for Impact explicitly values real-world outcomes. Business school rankings like the Financial Times Responsible Business Education Awards now track societal contribution.

Still, most tenure systems and funding schemes aren’t designed for real-world complexity. Until metrics evolve to capture impact across policy, commercial, civic, and cultural domains, researchers will face trade-offs that distort their choices.

5. No Translation Layer

Between discovery and delivery lies a dangerous gap. Without a translation layer, promising research can die before it impacts the real world.

Research translators come in many forms: tech transfer officers, accelerators, science communicators, knowledge brokers, and community champions. D’Este and Perkmann (2010) found that while commercialization is one motive, many academics engage with industry to gain access to practical data, funding, and collaborative learning opportunities [8].

Martinez et al. (2019) conducted a scoping review of evaluation methods for stakeholder engagement, finding that many efforts remain unevaluated or inconsistently assessed [9]. This applies not just in health policy, but also in product co-design, civic partnerships, and data governance.

Between discovery and delivery lies a dangerous gap.

Without translation, research remains “promising” rather than “in use.” We need people, processes, and platforms to turn insight into implementation.

6. Poor Timing

Even when research is clear, useful, and well-communicated, it can miss its moment. Timing matters. As I argued in Agile Strategies for EU Funding, traditional funding cycles often misalign with fast-moving market shifts, political movements, or current events.

To address this gap, new methods like rapid reviews and living systematic reviews have emerged to deliver timely, actionable insights without compromising rigor. Tricco et al. (2019) show how these approaches can support health systems under pressure by adapting review methods to fit urgent decision timelines [10].

The WHO’s 2025 Global Research Agenda on Knowledge Translation calls for better infrastructure to match the pace of public needs. But the same applies in markets: a missed product cycle or funding call can set innovations back years.

We don’t need to rush every study, but we do need pathways that let timely evidence meet timely demand.

Clearing the Path to Impact

Impact doesn't happen by accident. It requires intention, infrastructure, and alignment. As we've seen, even the most rigorous research can be sidelined by hidden frictions: poor framing, limited discoverability, weak relevance signals, misaligned incentives, missing translation layers, and bad timing. These aren’t just academic concerns. They’re obstacles to real-world progress, whether the goal is influencing policy, launching innovations, or improving lives.

To make research matter beyond academia, we need to be more deliberate about how it's framed, shared, and supported. Here are six ways to reduce friction and strengthen the impact pipeline:

- Frame for relevance: Position research in terms that speak to societal, commercial, or policy priorities, not just academic disciplines.

- Improve visibility: Use open access, clear metadata, and accessible formats to help diverse audiences find and understand your work.

- Signal applicability: Highlight practical implications, use plain language, and connect findings to current challenges.

- Align incentives: Push institutions and funders to recognize and reward engagement, co-creation, and broader forms of impact.

- Build bridges: Collaborate with knowledge brokers, practitioners, and industry partners to ensure findings are usable and contextualized.

- Move with urgency: Develop agile methods and partnerships that allow evidence to reach the right people at the right time.

Reducing these barriers won’t guarantee impact, but it will make it possible. And in a world facing urgent challenges, that possibility is worth pursuing.

Help Shape What Comes Next

I’m exploring how to remove the hidden barriers that keep good research from making a difference—whether in policy, practice, or products. By learning from people who care about impact but run into friction, I aim to plot the innovation landscape and knock down barriers to impact.

If you identify with the barriers in this post, I’d love to hear your story. Together, we can build something better.

Citations:

- K. Oliver, S. Innvar, T. Lorenc, J. Woodman, and J. Thomas, “A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers,” BMC Health Services Research, vol. 14, no. 1, Jan. 2014, doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-2.

- J. Schot and W. E. Steinmueller, “Three frames for innovation policy: R&D, systems of innovation and transformative change,” Research Policy, vol. 47, no. 9, Nov. 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.08.011.

- H. Piwowar et al., “The state of OA: a large-scale analysis of the prevalence and impact of Open Access articles,” PeerJ, vol. 6, p. e4375, Feb. 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4375.

- T.-H. Chiu, H.-L. Chen, and E. Cline, “Metadata implementation and data discoverability: A survey on university libraries’ Dataverse portals,” The Journal of Academic Librarianship, vol. 49, no. 4, pp. 102722–102722, Jul. 2023, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2023.102722.

- P. Glasziou et al., “Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of biomedical research,” The Lancet, vol. 383, no. 9913, pp. 267–276, Jan. 2014, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)62228-x.

- K. Oliver and P. Cairney, “The Dos and Don’ts of Influencing Policy: A Systematic Review of Advice to Academics,” Palgrave Communications, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1–11, Feb. 2019, doi: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0232-y.

- E. Sormani, T. Baaken, and P. van der Sijde, "What sparks academic engagement with society? A comparison of incentives appealing to motives," Industry and Higher Education, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 19–36, Feb. 2021, doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0950422221994062.

- P. D’Este and M. Perkmann, “Why do academics engage with industry? The entrepreneurial university and individual motivations,” The Journal of Technology Transfer, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 316–339, Feb. 2010, doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-010-9153-z.

- J. Martinez, C. Wong, C. V. Piersol, D. C. Bieber, B. L. Perry, and N. E. Leland, “Stakeholder engagement in research: a scoping review of current evaluation methods,” Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research, vol. 8, no. 15, pp. 1327–1341, Nov. 2019, doi: https://doi.org/10.2217/cer-2019-0047.

- E. V. Langlois, S. E. Straus, J. Antony, V. J. King, and A. C. Tricco, “Using rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems and progress towards universal health coverage,” BMJ Global Health, vol. 4, no. 1, p. e001178, Feb. 2019, doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001178.